When I was a kid, Labor Day was always symbolic of the absolute last day of summer. The new school year usually started the following day. We always had a BBQ on Labor Day. It was mostly a quiet time spent with family, and certainly nothing too eventful where I would list it in my obligatory “What I Did This Summer” first-week-of-school essay. However, the day was relaxing and a gentle way to wind down the summer.

I entered the workforce when I was a teenager, my first job being a dishwasher at a local café. My pay was $4.00/hr., under the table. After that, other jobs I took were in a retail setting. Living in New Jersey, a job that involved working at a mall was considered cool amongst adolescent peers (Jersey is kinda known for its malls and diners). Obviously, the mall is open on the holiday – there are lots of great sales! Alas, my sophomoric mind’s logic thought that as laborers, we should not work on Labor Day. If I could go back in time, I’d slap my naïve self. I’ll get back to this thought later.

As I aged, I noticed that not many people knew what Labor Day is and its history. And like most origin stories that are filled with strife that builds up to the tipping point of existential climax, Labor Day’s origin story does not disappoint.

Labor Day Officially Means. . .

The holiday usually conjures the idea of barbeques, parties, retail sales, back-to-school, and the unofficial end to summer. But was does it really mean? According to the US Department of Labor, Labor Day means “a creation of the labor movement and is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers. It constitutes a yearly national tribute to the

Why Do We Have Labor Day?

The short, anti-climactic answer – because Grover Cleveland failed to end a railroad strike. It became a federal holiday in 1894 to act as

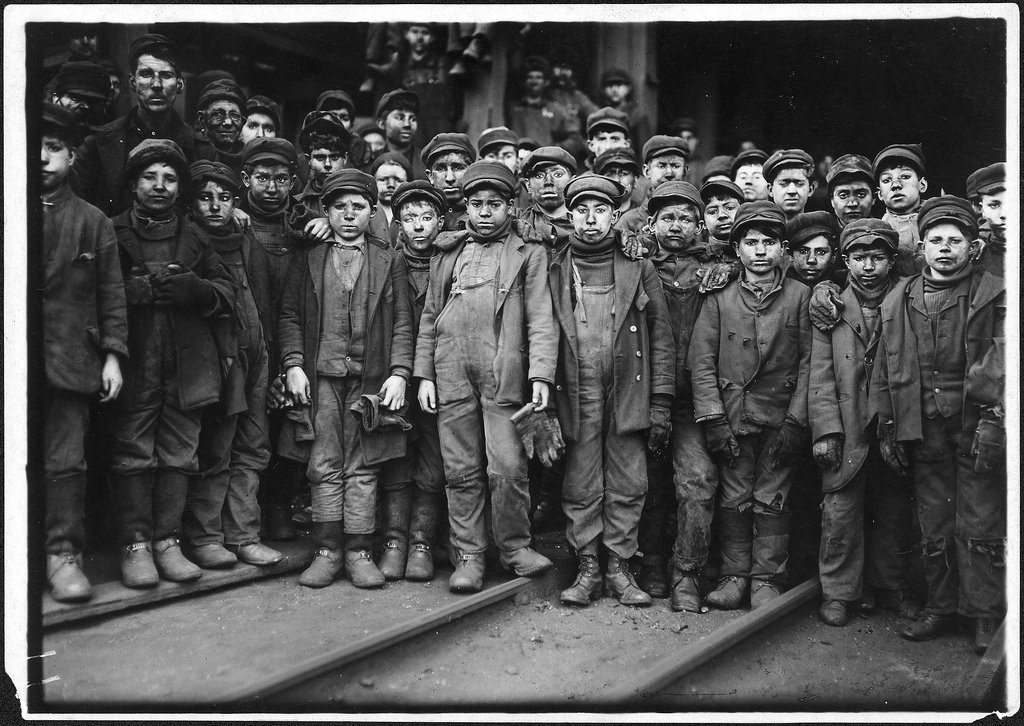

But to settle with the short answer robs us of the experience of turbulent changes during the late-19th century. “At the height of the Industrial Revolution. . . the average American worked 12-hour days and seven-day weeks in order to eke out a basic living. . . Children as young as 5 or 6 toiled in mills, factories, and mines. . . earning a fraction of their adult counterparts” (History.com Staff, 2010). During this time, working conditions were a nightmare. Imagine working in a factory, choking on stagnant, hot air, while, quite possibly, drowning in your own lungs from consumption. Or working in a meat-packing plant without separate running water to wash your hands, thereby washing your hands in the same water used to make sausage (as illustrated in the fictional work of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle). And, for a moment, entertain the idea of working under these horrid conditions without any breaks. People had enough and they organized labor strikes. Can you blame them?

Suggested to be one of the first Labor Day parades, “on September 5, 1882, 10,000 workers took unpaid time to march from City Hall to Union Square in New York City” (History.com Staff, 2010).

One of the most notable strikes that prompted labor reform was the Haymarket Riot of 1886. It was a “violent confrontation between police and

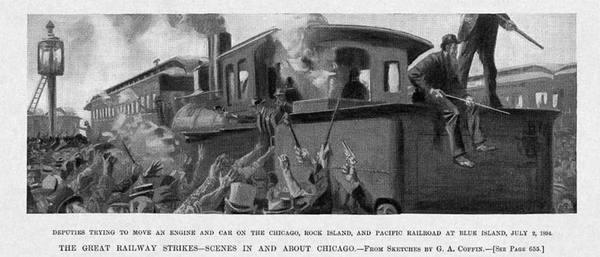

It is difficult to fathom the hardship that workers of the 19th century went through. The conditions surrounding the Pullman Strike of 1894 were highly volatile substances waiting for a spark to cause a transformative explosion. First, let’s set the scene. As mentioned, it’s 1894. There’s an economic depression. Pullman, who peddled luxury railroad cars, decided that the way to cut costs was to lower employee wages. While much of Chicago’s businesses lowered wages, Pullman took it a step further. After cutting wages by 30%, Pullman refused to lower rent and living expenses for his workers on his properties. Workers were beyond irate – and understandably so. Pullman’s workers were unable to support their families. When the workers finally did strike, Pullman refused to speak to them. He wouldn’t meet with his striking employees to come to some accord at all. The strikers received some support from the community and other railroad organizations. Striking and boycotting railroad workers crippled travel. Soldiers were sent in. And it only got worse (Cain, 2017).

Violence raged as Chicago swelled with soldiers and strikers clashed with troops on railroads across the west. Federal forces went city by city to break the strikes and get the trains running again. In the end, 30 people died in the chaos. The riots and sabotage caused by the strike ultimately cost $80 million in damages

Áine CainAs a result, Labor Day became a federal holiday after Grover Cleveland failed at breaking up a railroad strike in 1894. While the holiday’s founders are subject to debate, the suggested founders are either: Peter M. McGuire, co-founder, American Federation of Labor; or Matthew Maguire, secretary, Central Labor Union (History.com Staff, 2010). Labor Day was created “as a conciliatory gesture toward the American Labor Movement” (Urofsky, n.d.).

The workers who risked their livelihood and lives are the heroes of the labor movement. Without their tenacity and courage, it is hard to imagine how work would be today. It’s frightening and awe-inspiring.

As I mentioned, today’s work dynamic has changed drastically since the late-19th century. After I

I’m finally in a position where adult me can relax on Labor Day and spend it with my family. Bring on the BBQs and parades. And THANK YOU to those who made it happen. Happy Labor Day!

References

Cain, A. (2017, September 2). The US celebrates Labor Day because of a bloody clash over 100 years ago that left 30 people dead and cost $80 million in damages. Retrieved from Business Insider: https://www.businessinsider.com/labor-day-history-2017-8/

Coffin, G.A. (1894). Deputies Trying to Move an Engine and Car on the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad at Blue Island, July 2, 1894. Harper’s Weekly Magazine. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PULLMAN07.jpg

Hein, Lewis. (1911). Breaker boys working in Ewen Breaker. S. Pittston, Pa, January 1911. [Photograph]. National Archives at College Park. Retrieved from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/usnationalarchives/7496283770

Hein, Lewis. (1908). The overseer said apologetically, “She just happened in.” She was working steadily when the investigator found her. The mills seem full of youngsters who “just happened in” or “are helping

History.com Staff. (2010). LABOR DAY 2018. Retrieved from History.com: https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/labor-day

In The Story of Pullman, 1893. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Workers_leave_the_Pullman_Palace_Car_Works,_1893.jpg), “Workers leave the Pullman Palace Car Works, 1893”, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Template:PD-old

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Haymarket Riot. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/event/Haymarket-Riot

Urofsky, M. I. (n.d.). Pullman Strike. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/event/Pullman-Strike

US Department of Labor. (n.d.). History of Labor Day. Retrieved from US Department of Labor: https://www.dol.gov/general/laborday/history